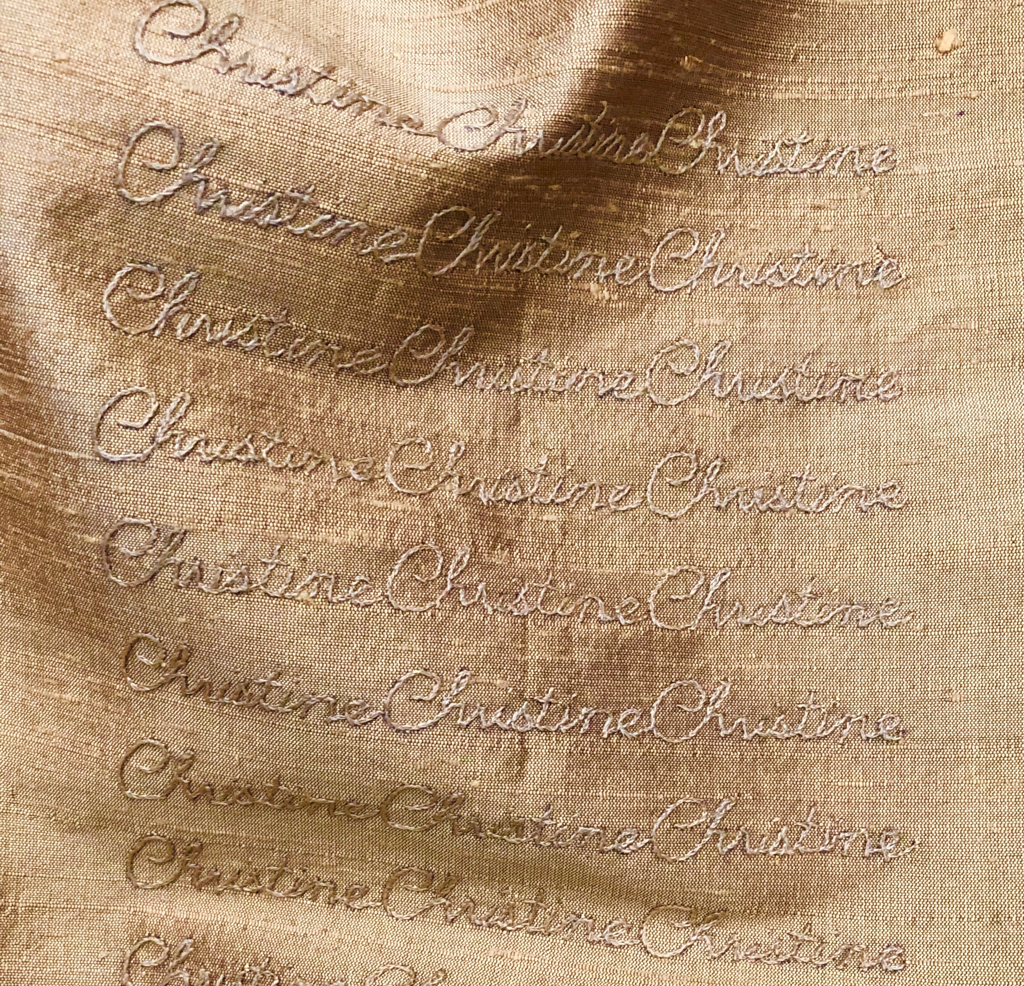

Dear Christine - A tribute to Christine Keeler

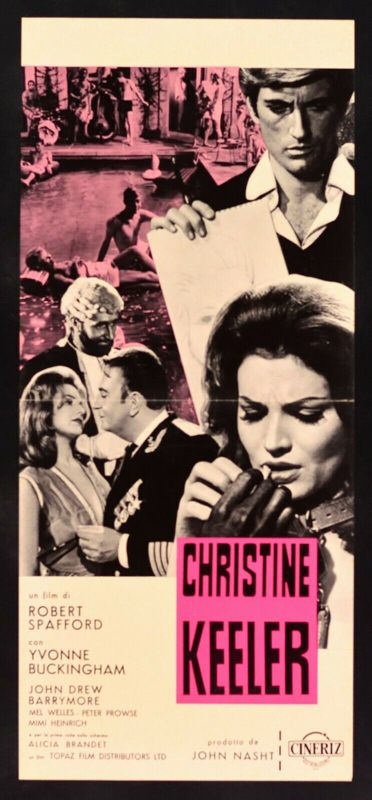

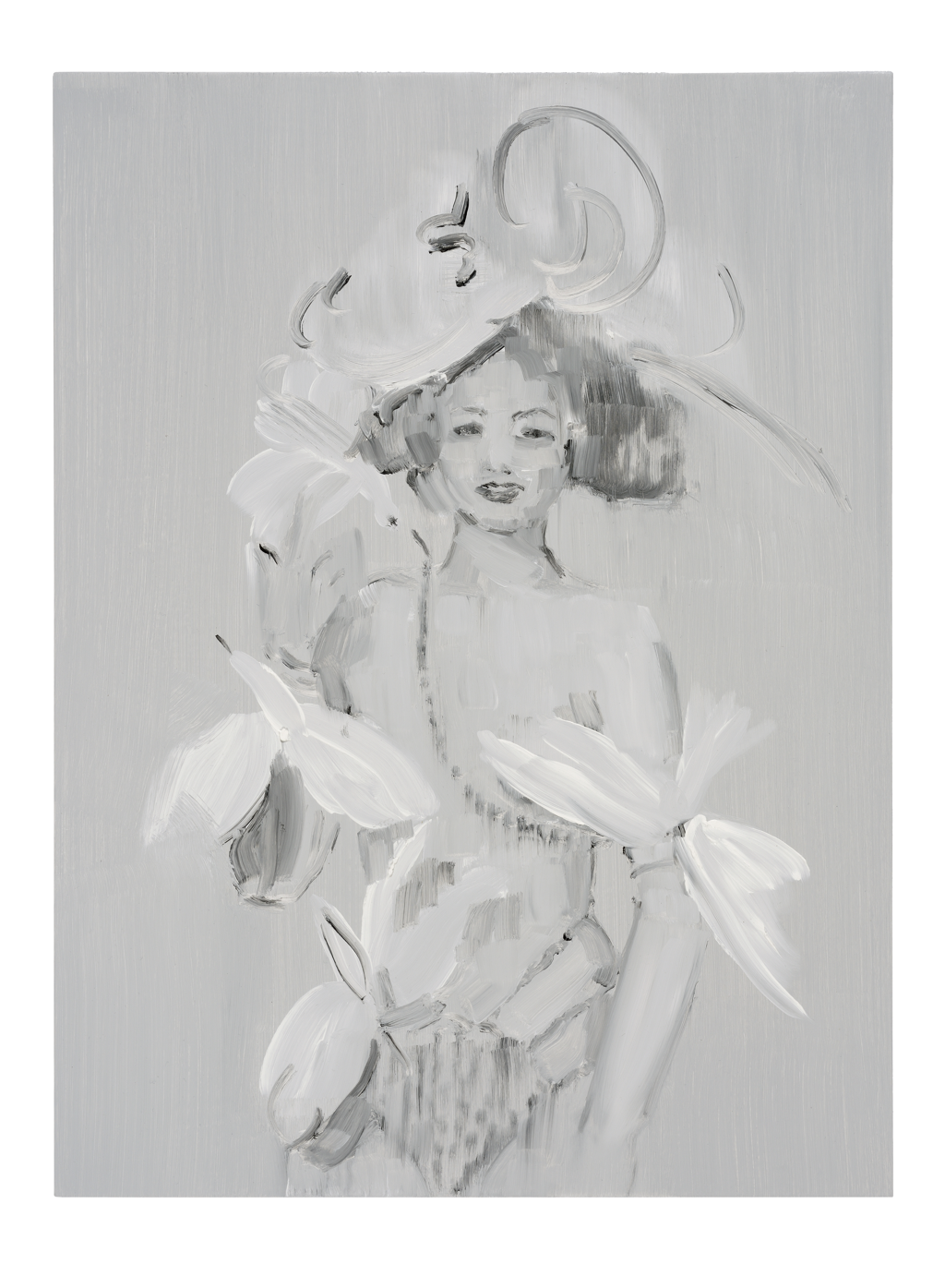

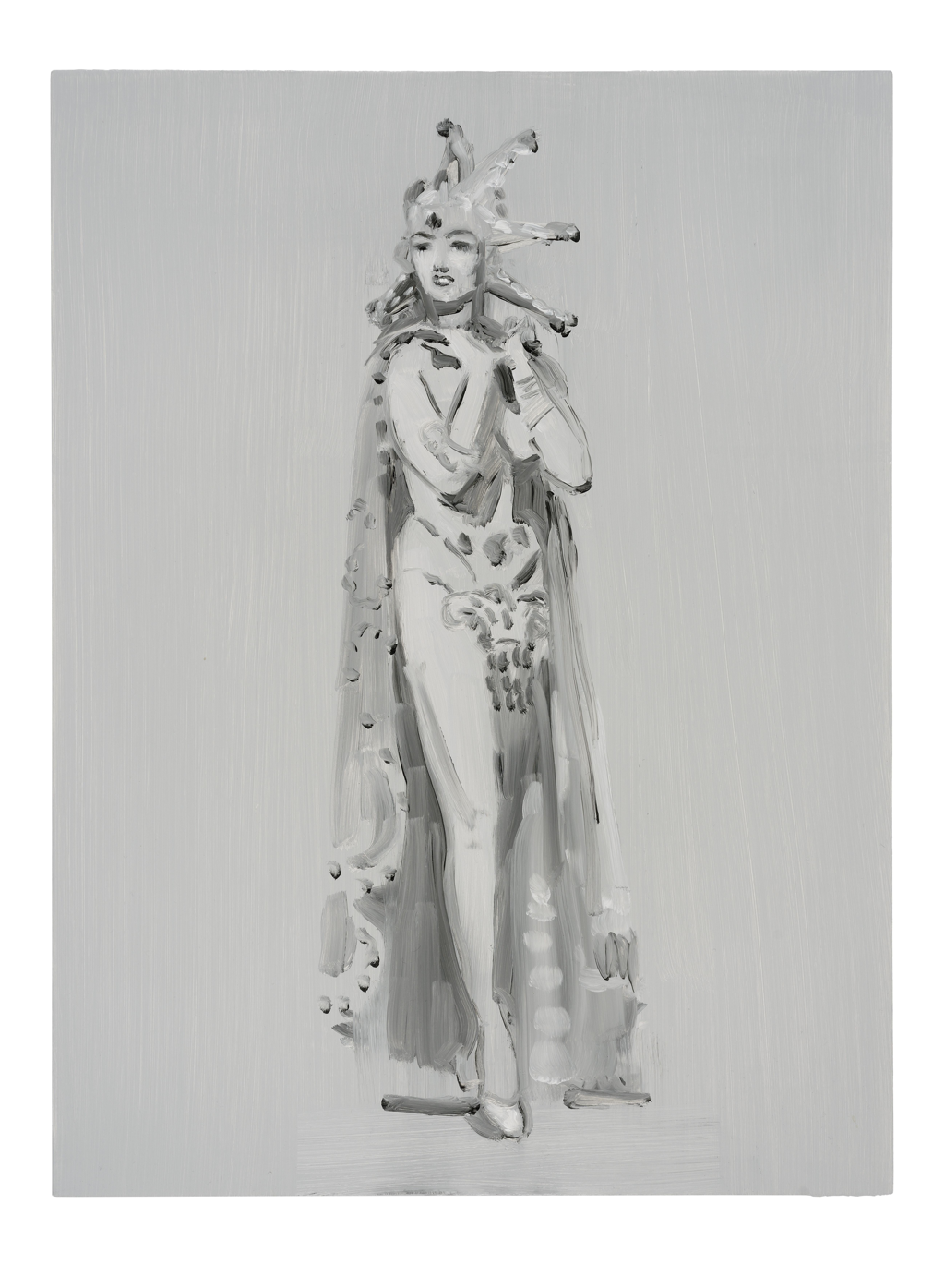

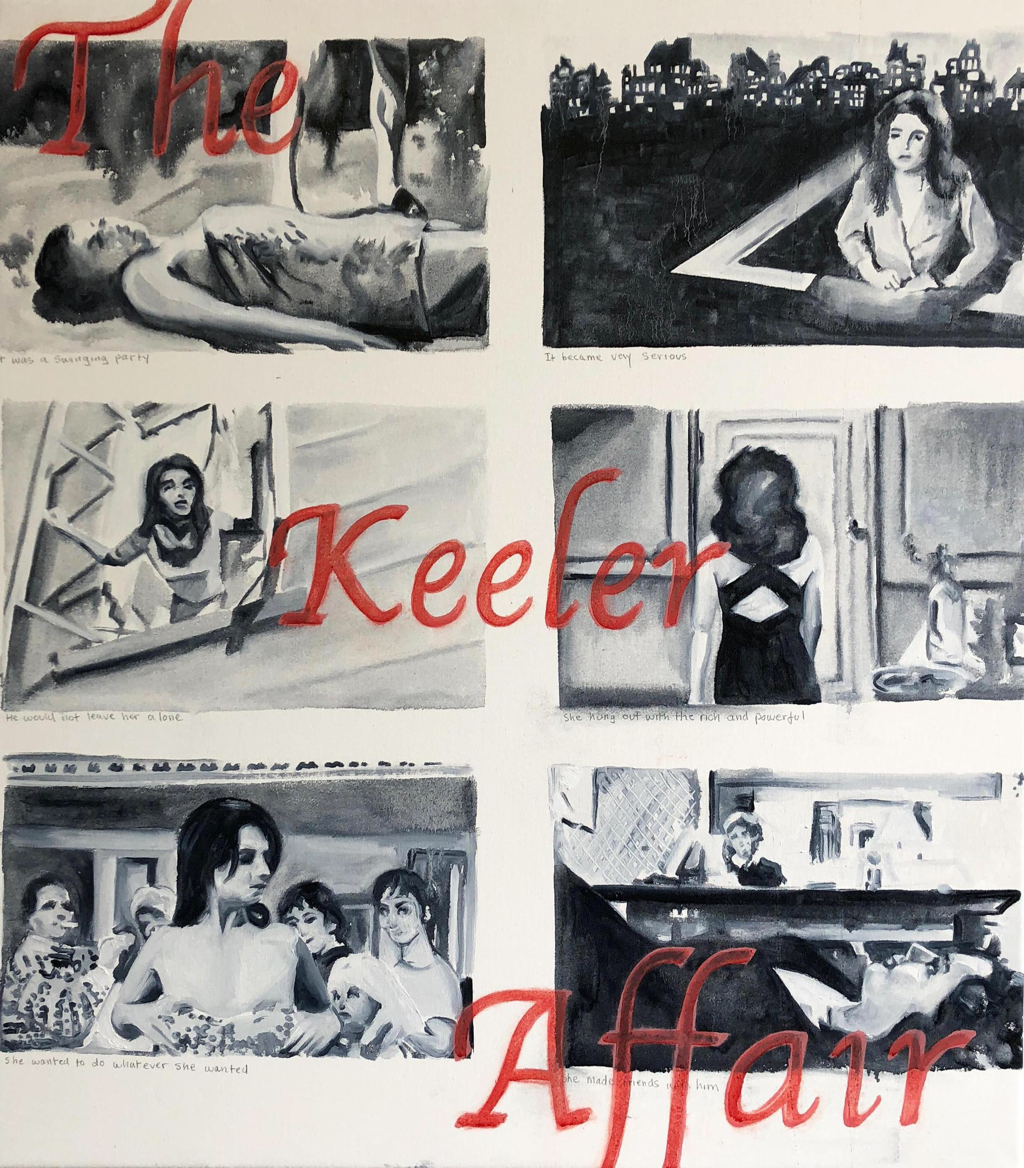

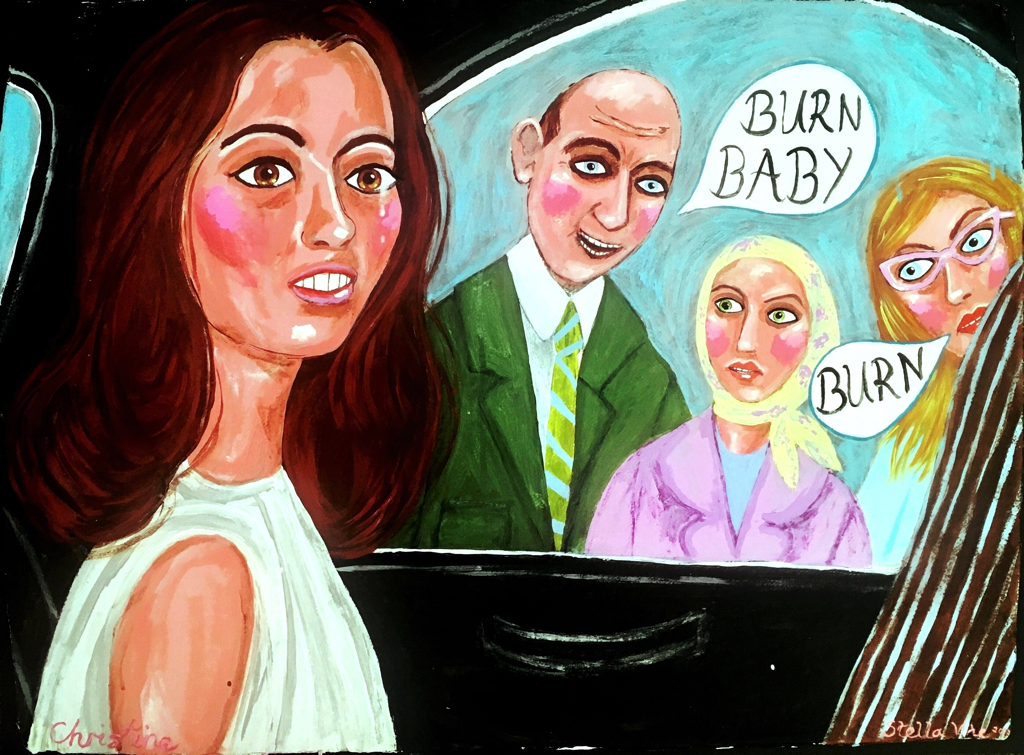

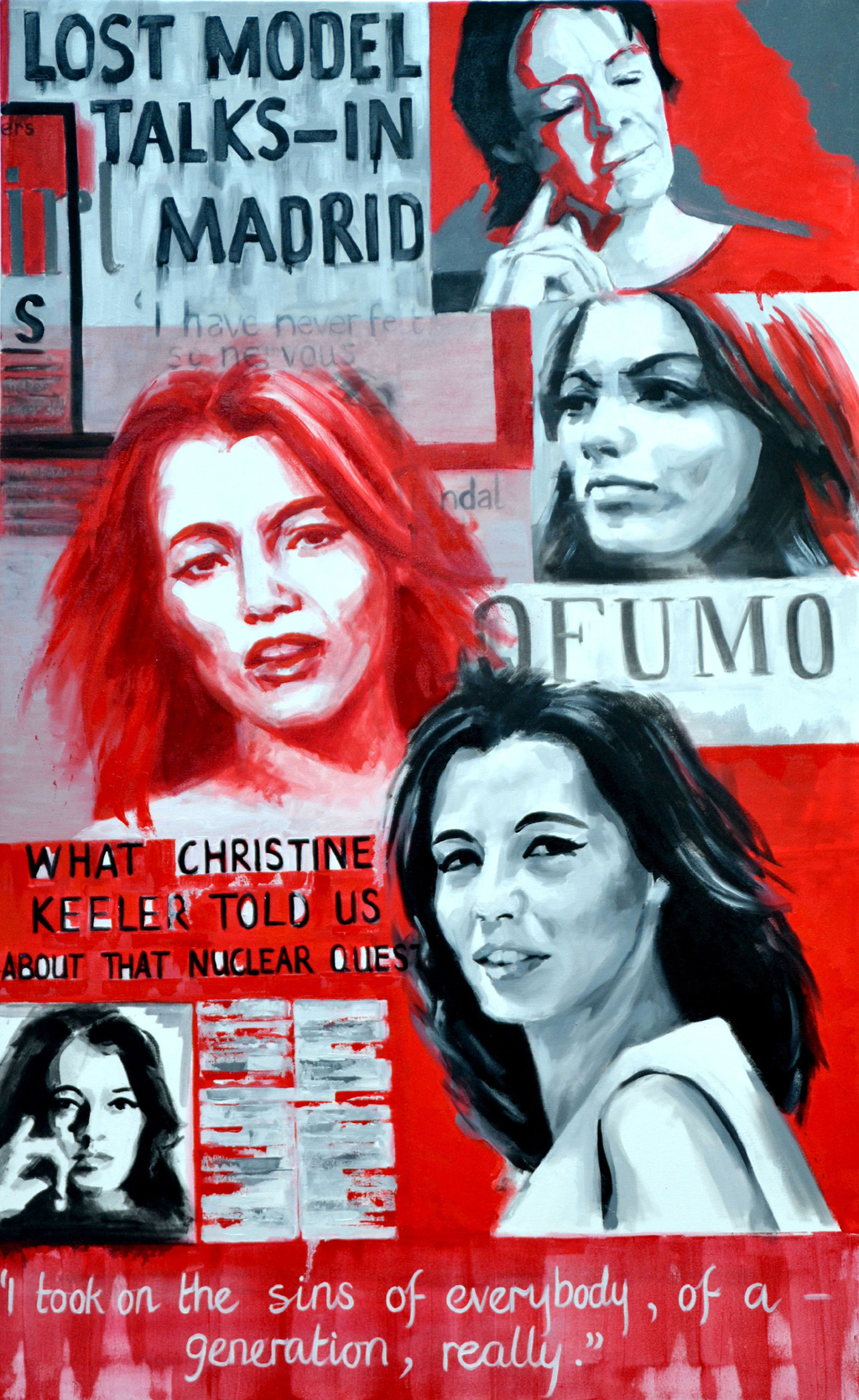

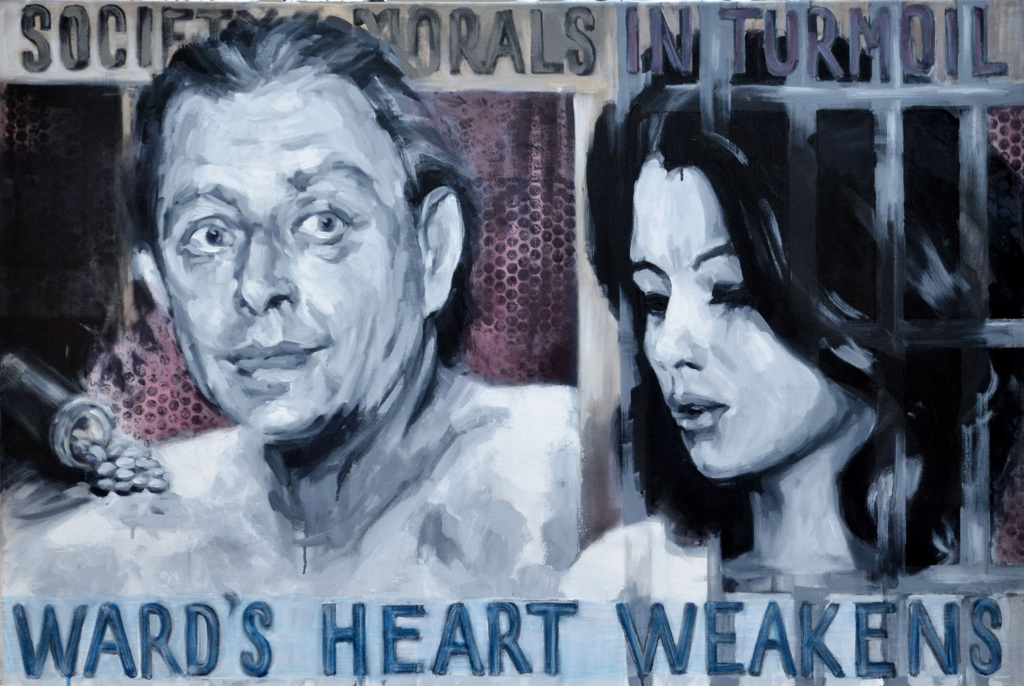

Arts Council England supported a tribute to Christine Keeler, which opened at Vane Newcastle upon Tyne in June 2019 before touring to the Elysium Gallery in Swansea in October 2019 and ending at Arthouse1 in London in February 2020. Artist and curator Fionn Wilson's four-year project to reclaim and re-frame Keeler and featured artwork from 20 female artists working in poetry, music and performance art.

Music

'Dear Christine' is a composition for solo cello paying tribute to Christine Keeler, commissioned by curator Fionn Wilson and composed by Katie Chatburn

|

"My composition ‘Dear Christine’, draws upon all the paintings in this exhibition and is an emotional response to the narrative of Christine Keeler’s life. The refrain reflects being ‘caught in a loop’, as it struck me that variations on Christine’s story still play out across society - in politics, in the media and our workplaces.

But at the heart of it is a sense of incantation or a prayer for Christine, melancholy, fragile, but infused with hope and dignity in the face of such overwhelming pressure." Katie Chatburn, May 2019 |

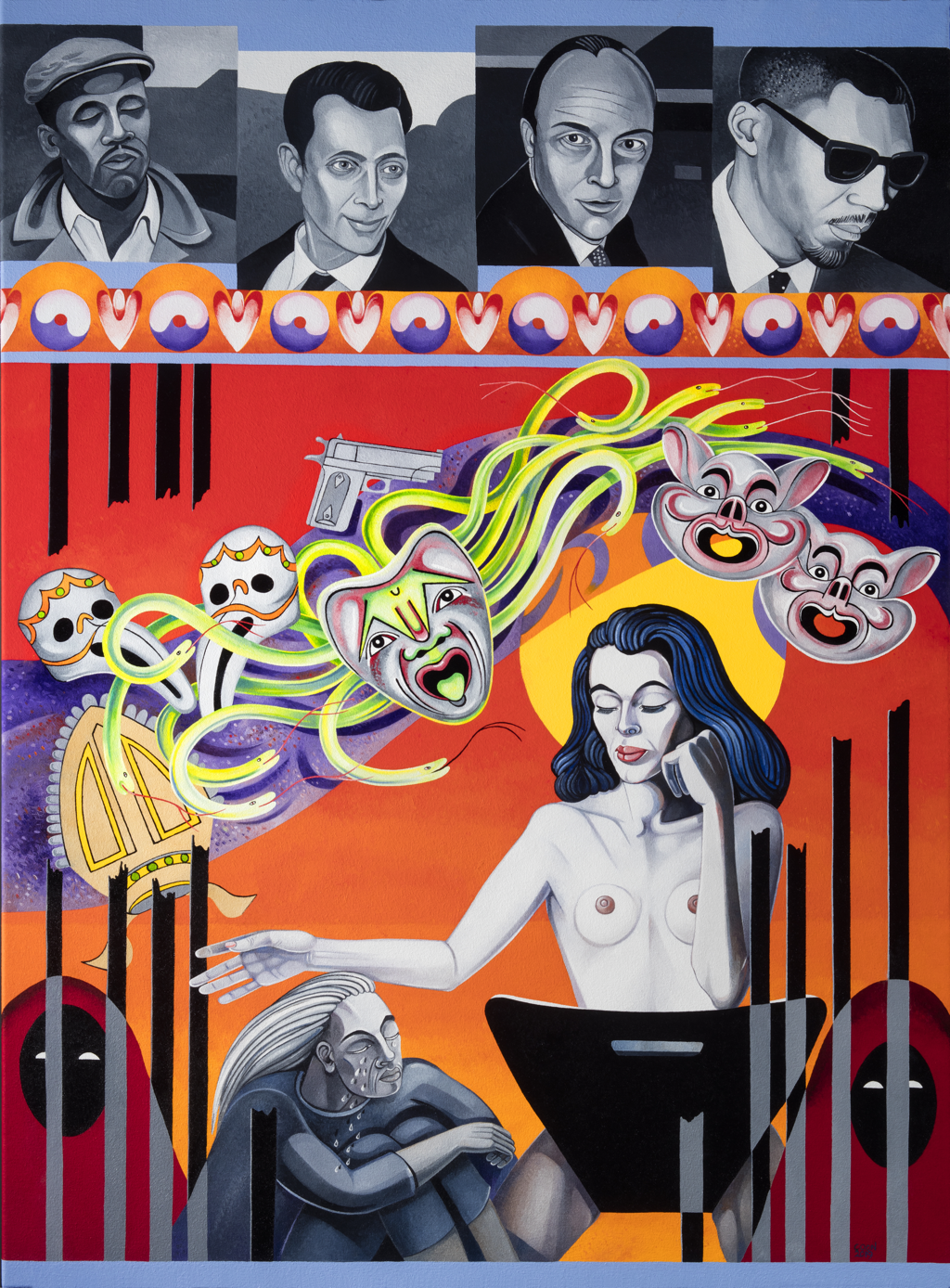

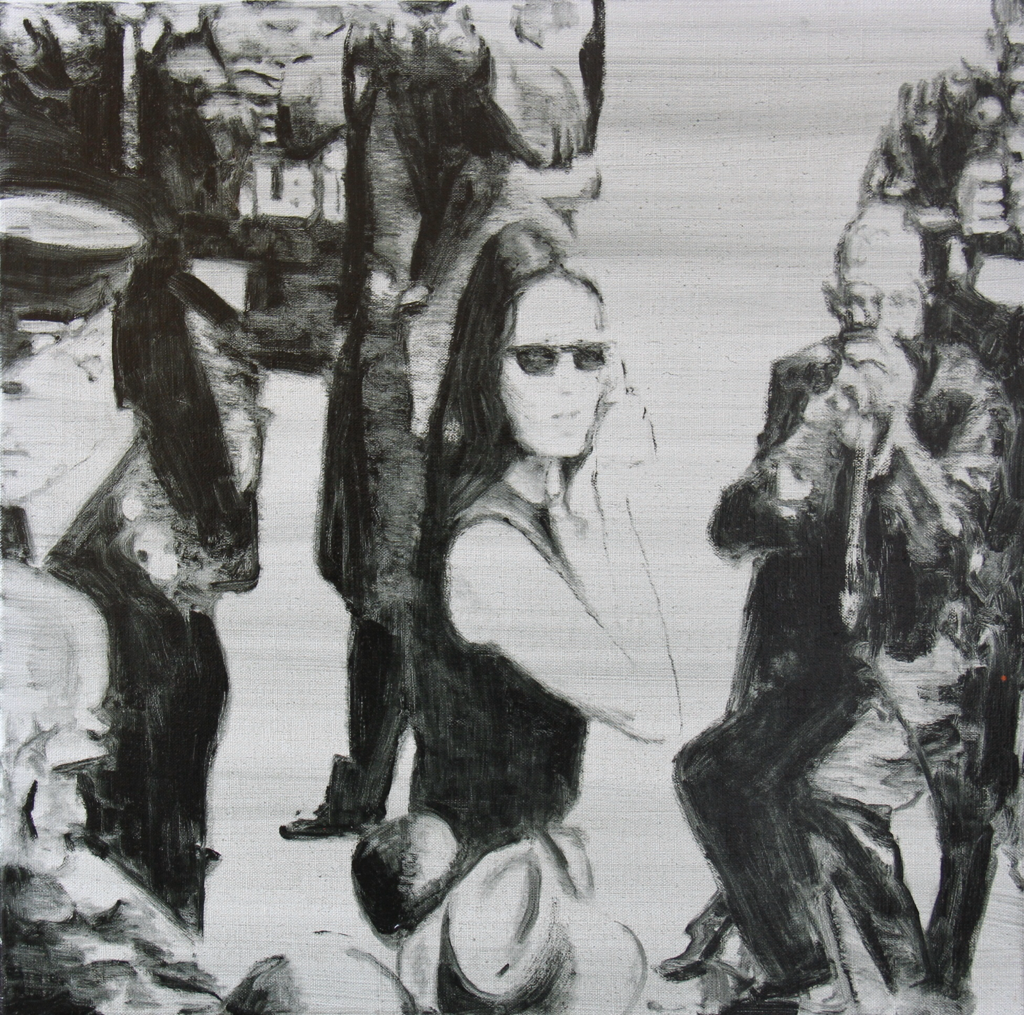

Catherine Edmunds - "Christine Speaks", 2016

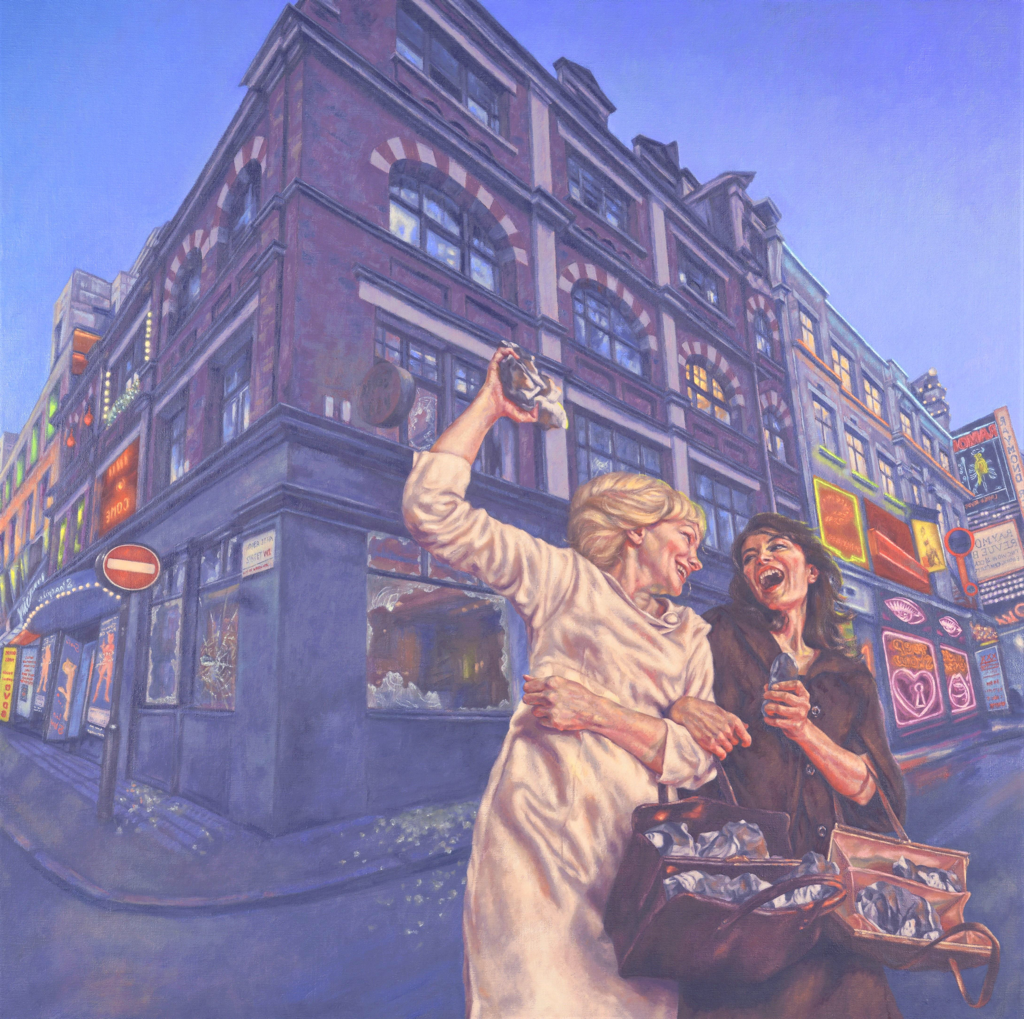

Marguerite Horner - “Casting the first stone”, 2017

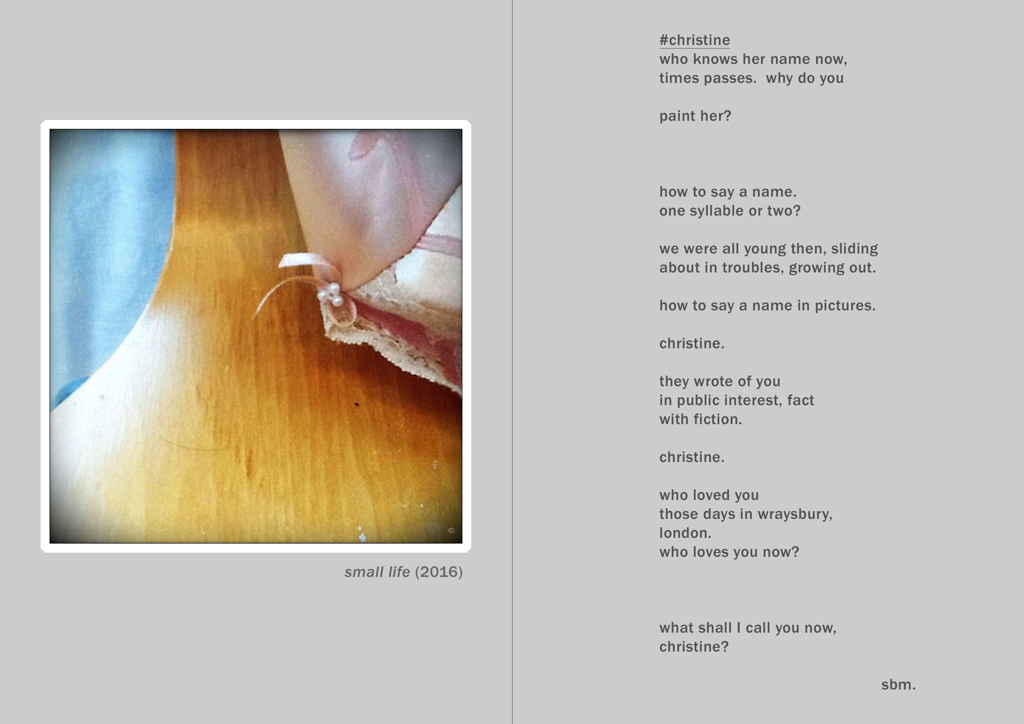

Poetry from "Dear Christine"

|

Railway

(i.m. Christine Keeler) An abandoned bus on a farm, a derelict boat beached beside the river, a summer house that swivels on its rusted base to face the sun, an old railway carriage. Living there, free, secret This is a child’s game. The train travels along the coast the sea gleaming and shivering, the herons watching in the sand, people digging for lugworms. The girl living in the carriage is going somewhere. She dreams of possibilities, of maybe and perhaps. A child’s play, full of bravery and risk. But in a boat that is beached, a broken bus, a railway carriage marooned away from the sidelines it is hard to get away. Through the cracks in the deck to the holes in the walls, through the cracked glass of the train windows the old intruders – Cold, and Frightened, and Lonely – sneak in, desperate for love. The girl living in the carriage is going on a journey. She doesn’t know where it will end. Jeni Williams |

Historiography

If Christine Keeler was discovered in Pompeii Would they say that because her ghost-shape Was found outside the Lupanar She was a prostitute? This, they say, is a woman of the brothel Because of how she fell – Sumptuous, unfolded, extravagant. Yet the same fallen pose Could be read otherwise. She might have been a visitor to the house Of pleasure, merely there To deliver fishes, olives, peaches, bread The wide basket of her thighs Open to speculation only. Jo Mazelis |

|

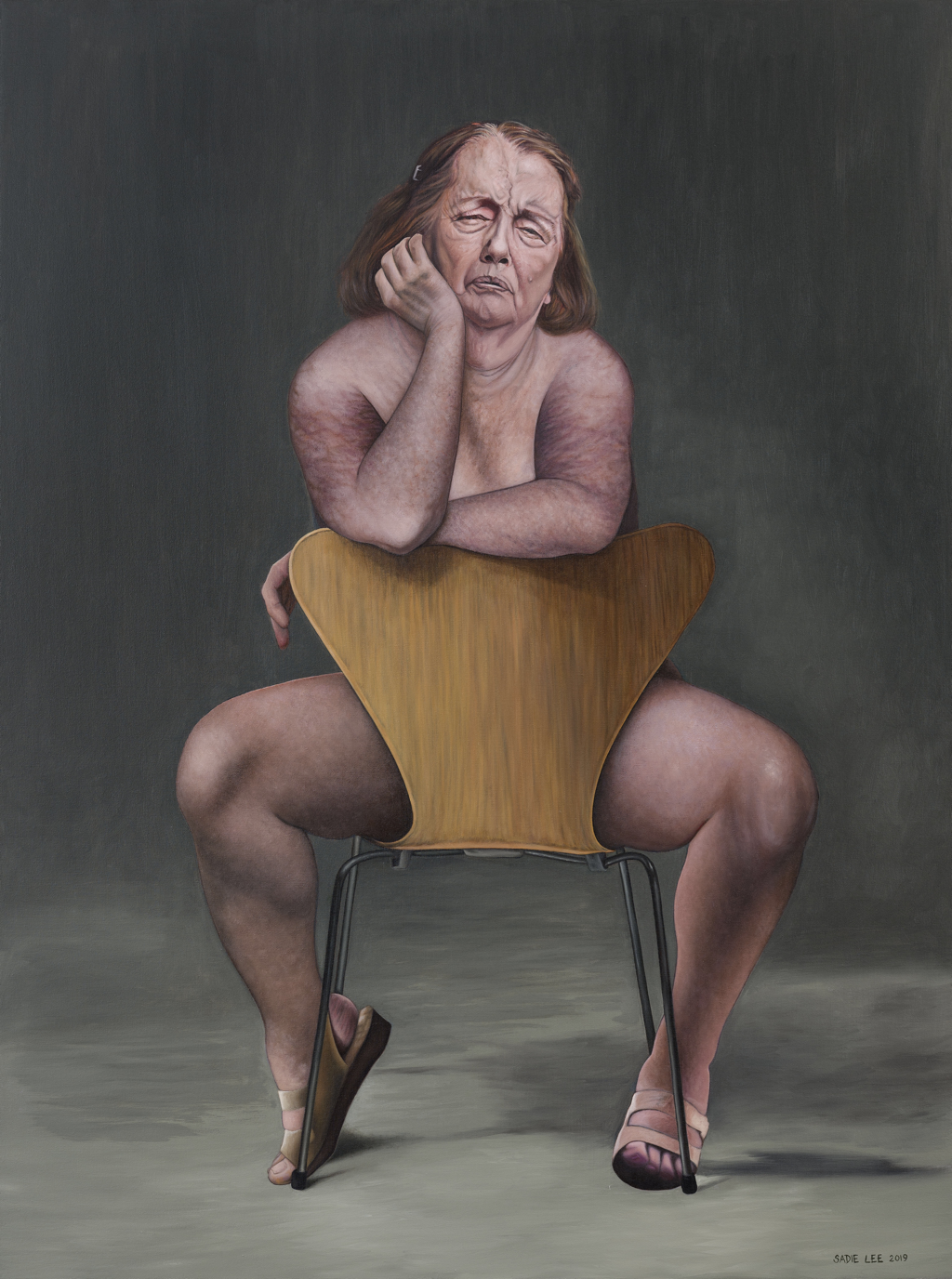

Christine’s chair

Draping this chair since 1963 I’ve bled over the veneer, aging, critically prettily, contemplated pills to end it – less chaos. Less mess. This room is stuffed with people, simmering agendas, quests for cash. or secrets or women wanting tips on the art of posing for so long, without going numb. They go. I’m left, stamped – an un-sent letter, yellowing, bit-by-bit as the world decides whether to release me. Bring in the fruit I crave, brimming from the corporate pot, lead me to warmer rooms, give me an iron shot. Take me back to that child’s heart – where fear was reducible and didn’t move me to the deep black eye of the periphery, I’ve delivered and lost life in this triangle pose, from God’s grace – a dead-bad fuck. Tiny immaculate womb, pushed up against wood; beautifully rationed hips – spilling, from the waist of it. |

In that unclaimed corner, I’ll dig out a temple, bury a set of scriptures, my foetuses, call the truth of my life; grow stronger legs from squatting to tend the gully, to be a wife, wolf-bitten lips and old pearls Come! Don your boss face, puff up your chest, decorate my wrists in flower cuffs. Twist my forearms to your needs, unpeel my skin from the sweat-stick of this long sit. I need to see the faces of women below, outside this ‘Establishment Club’, laughing in the smoke rings, imagining the babies declining, easy flings. I’ll remind them – sex is not lethal every time. Open your medicated legs, but think of our England, my girl-youth, that cool, numbing abuse, all the precisely wed, the quick whores – identical screaming, turning. their backs diligently, in service to that dog-tired man. look. This chair, with its long bones and hidden arches is my legacy. I’m nailed in, flesh and limbs printed for the programme, naked or not. |

I’ll speak through the angle of my neck now, a pause, a brow twitch to the east, hold my lips for the next man, for peace inside these cold walls, this occupation. They visit still when it suits business, to feed off my look, for a spank, a smooth, a stolen hour, for rejuvenation Mute in my box – dancer, bird, I wait for light, for air to stir through the slowly clouding panes, to bring me feathers to weave a head-dress, a rainbow robe from the monochrome. Empress-goddess. Girl-birther. Sentry-woman. Cabaret-lass – clasped as his metal still rolls out weapons, digital death, acid attacks. I’ll stay, keep staying – stay here for his return, smile, loosely for the camera, straddling under this bulb, his contract. Guinevere Clark |

|

Found poem 1980

(every word spoken by the interviewer except those marked with * told by Christine Keeler, the interviewee) Keep her end up £400 a month what can you bring to men only readers how can you help them? Do you regard yourself as particularly sexually experienced? The name Christine Keeler A bygone world Led to death of one Disgrace of another Departure of anothert Nearly brought the government down Security threat led him to admit the truth Were you in a position to spy Face turned a hundred heads in political farcical sexual comedy of manners What have you learned from the failure of your two marriages both of which didn’t last long Do you feel that the break up was your fault? None of them either lasted very long? Both ended very quickly Do you expect to meet the right one? How do the children live with your past? This is the first television interview I have ever given Newspapers would never speak to me If you wanted to forget the Christine Keeler and what happened in 1963 You wouldn’t be selling that name now would you? *Well as I said..... Publish and be damned is that what your motto would be? *Yes yes yes Patrick Jones |

The pieces

Magnum of champagne—knitting needle—Soho rain— Murray’s Club—a railway carriage—the bromide print— the baby, the baby, and all that blood-- you, crying out—you, crying out with joy, driving in a car— with Stephen—the bend of a country lane-- your hair breezing-- the revolution will shortly begin-- your lovely legs will straddle what is not an Arne Jacobsen— Series 7—your face remain inscrutable-- as you regard-- your face in that photograph— the architecture of paradox-- Lucky had an axe-- Johnny fired a gun five times at the lock— now you rise in the dock-- all the stories you’ve told—as you draw the curtains— the ghostwriter sets down-- his tape recorder-- when you pose for Stephen-- his elegant hand across the paper-- what a tender, brutal self-deceit is captured-- remember when—the axe—the gun—or the Series 7— you straddled—not an Arne Jacobsen—not knowing fully, then, what’s in a name—Eugene or Jack-- you, crying out—crying out in pleasure-- crying out in pain—you, rising-- from the pool—that rent-red, summer-evening sky-- at the job interview-- remember your name—what’s in a name— assemble the pieces you own—hesitate-- take his hand-- ‘Christine Sloane,’ you-- say—smooth down your skirt—and sit-- Kathryn Gray |

|

A hand to play

(for Christine Keeler) The hand built her a bike before she could ride it. She took it to peddle it to the corners of his grainy world. The hand opened her up to boys. She breathed fires, conquered trees, rough ‘n’ tumbled with tombstoning Tom, Dick & Harry. The hand stuffed her with fibreglass then stitched her with thread so, she daren’t tread beyond hunger from his bed. Until, teen-bled, no script, unwed, she ended up with a baby gin-dead. |

With the hand’s final word, she rode across borders, without tracks, to the window of eyes, to be a fashion sketch, of Mary Quant size. The hand of rule caged her, paraded and staged her for the Scalps, and Suits slapped her gem-wax buttocks, smoothed her polished thighs: a mannequin, a plaything for snollygosters in loose neckties. The fateful dip in a skinny pool, nude, beneath a lecherous moon. |

She was handed to the stiff with an upper-crust lip. Was it kismet? Was it just a blip? After her postcoital cigarette, slithers of glass pushed from within; grew from her cheek, from her lids, from her tits, to score the crease of his pillowed peck. Cold blood cast a shadow of war between them. |

She invented sex in the sixties where the odd squeeze, translated to sleaze. News-hacks picked at the lauded titles’ bricked wounds; where landed ranks of peevish prudes were toppled by a tiny teenage termagant from the wrong side of the divide. Gemma June Howe |

|

Flash

(Christine Keeler astride an ‘Arne Jacobsen’ chair, 1963) A sunless studio in Soho. Smoke curling the stairwell. Trumpet creeping like vines from the ground floor. Flash. I did as I was told. Stood stripped and bare as a new-born foal. Straddled the chair. Leant into its unyielding grain. Fizzed at its rigid geometry. The way it cinched at the waist, shielding the softest parts of me. The powdery folds of my belly. Glared at the camera lens like a lover. Unabashed. In just twenty nine frames he captured every fragment– my upper lip bowed like a harp. The small crease between my eyebrows like the pleat of a bed sheet. Defiant wrinkle pressed to my nose. Later, they listed all the men I’d taken to bed. Asked, are there any who you have actually loved? Are there any who loved you? Mari Ellis Dunning |

Like me

—for Christine Keeler (1942-2017) Like me, you were a tomboy, climbing trees, riding your rusty bike by the river, knees muddy, playing with boys. One mum or dad captured in black and white a look you had— aside from plaits and overbite—the ease of a child at home in herself, smiling to please no one. But your stepdad stifled days like these, with his look, his hands, his friends. And you were glad, like me, to flee to London, where I thought books were keys to freedom but, like you at times, would seize the chance to make some foolish man mad for me. Adventuresome, we were, not bad, half wanting love, harbouring half-felt pleas: like me. Charlotte Innes |

Christine Keeler vs. The Crown

Put the record on, but make it backwards: The Prime Minister’s Crisis walks out of the Crown Court and down the steps, chin up, face on;

a regular Marie Antoinette, that bloody whore, that slinky party girl--

Let’s reverse it. It’s 1963, and Stephen sits in his apartment coughing barbiturates back up, the judge is

sitting and swallowing the guilty verdict down. It’s 1963, and when it’s over, Christine gets up, buttons up, and retreats out of Gordon’s apartment, unsuspecting. Keep going. The chair’s there, but then she’s gone: blink and you’ll miss her, in the spaces between the camera flash.

Now it’s 1961, so she climbs back down into Lord Astor’s swimming pool, chlorine-eyed. The water’s closing over her head. There she goes. Further:

It’s 1961, and the name Yevgeny is new in Christine’s mouth. Call her a call girl, and what could she know anyway? Further. Her first eight per week warm in her hand, the bite of the showgirl tiara against her scalp, rubbing her feet in a back room somewhere. More champagne, anyone?

Further. Her baby breathes again for six more days. Bring the puppies back up from the bathtub. Let’s leave the pen alone for writing. Let’s take the word perjury out of people’s mouths. It’s like they say. It’s like they always say, to showgirls, to babysitters, ten a penny girls drawn into London from elsewhere, who knows, who cares—what’s a girl got to be running from?

What’s nine months, to a woman? After all, nothing has been proved.

Sarah Caulfield

Put the record on, but make it backwards: The Prime Minister’s Crisis walks out of the Crown Court and down the steps, chin up, face on;

a regular Marie Antoinette, that bloody whore, that slinky party girl--

Let’s reverse it. It’s 1963, and Stephen sits in his apartment coughing barbiturates back up, the judge is

sitting and swallowing the guilty verdict down. It’s 1963, and when it’s over, Christine gets up, buttons up, and retreats out of Gordon’s apartment, unsuspecting. Keep going. The chair’s there, but then she’s gone: blink and you’ll miss her, in the spaces between the camera flash.

Now it’s 1961, so she climbs back down into Lord Astor’s swimming pool, chlorine-eyed. The water’s closing over her head. There she goes. Further:

It’s 1961, and the name Yevgeny is new in Christine’s mouth. Call her a call girl, and what could she know anyway? Further. Her first eight per week warm in her hand, the bite of the showgirl tiara against her scalp, rubbing her feet in a back room somewhere. More champagne, anyone?

Further. Her baby breathes again for six more days. Bring the puppies back up from the bathtub. Let’s leave the pen alone for writing. Let’s take the word perjury out of people’s mouths. It’s like they say. It’s like they always say, to showgirls, to babysitters, ten a penny girls drawn into London from elsewhere, who knows, who cares—what’s a girl got to be running from?

What’s nine months, to a woman? After all, nothing has been proved.

Sarah Caulfield

|

Gospel

Lost in a shrinking flat, radiators hissing, radio on low, you dab at your palms to stem the bleeding. Tangy red, spoiled apples, spilling their pips like scandal. A movie unspools from the VCR. Showgirl clenches a fist. Taken on the floor, in a hundred stabs, you’re someone else’s. Camera-kiss. Clapper-board. The stiffening journalist’s pen. A clothes horse straddles the kitchen, fugs the window with its nylon heat, a lover’s tie, his tongue pressed against the arch of your mouth. |

Showgirl, he calls you, sign tacked to your back like a cross -- howling across gossiping headlines, tantalising dog whistles, and yes, many will call you Showgirl, muddy your Keeler, whittle you down to a whisper, but as you snap back, the skin at your jaw is tight. Christine, you tell them, slapping away at the hand that catches your elbow, nuzzling its fingers into your hair, Christine, spitting paper, bone, gospel. Natalie Ann Holborow |